|

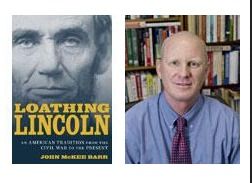

The Author of Loathing Lincoln Explains Why Some on the Christian Right Loathe Lincoln

Thus is seems like a good time to ask John McKee Barr, the author of one of this year's most informative books, Loathing Lincoln: An American Tradition from the Civil War to the Present for some insight into what is going on. As Barr told me before our interview, it is within the Neo-Confederate movement where the hatred of Abraham Lincoln and all he stood for meets the Religious Right. John Barr is currently a professor of history at Lone Star College-Kingwood [Texas], having joined their faculty in 2008. There he teaches a variety of courses including the survey of U.S. History, "Political Novels", "The Emancipators: Charles Darwin, Abraham Lincoln, and the Making of the Modern World," and "Revolution and Counterrevolution." His website can be found right here. Loathing Lincoln is his first book and an important first effort. The tome not only provides the reader with excellent insight into the to peculiar tradition of Lincoln hatred, but by extension, a more complete understanding of many of the beliefs that underlie the current nullification and secession movements. I began our conversation by asking Barr to explain Lincoln's religious philosophy. Was it unchanging or did it evolve over time? Barr: Lincoln's religion has been a topic of unending fascination, both for his admirers and his critics. For me, the best book on this subject is Allen Guelzo's Abraham Lincoln:Redeemer President. In broad terms, I think we can say that Lincoln grew up in a deeply religious world of Protestant Christianity. As Guelzo puts it, "Intellectually, he was stamped from his earliest days by the Calvinism of his parents." In addition, Lincoln certainly had what many have called a melancholic streak in his personality (Lincoln's "melancholy dripped from him as he walked" his law partner William Herndon said), and that too, at least in my view, shaped his religious beliefs. One of his favorite poems was by William Knox, one entitled "Mortality." A close look at that poem I think verifies the future president's dark outlook. Still, Lincoln did go through a phase of being what Guelzo calls a "religious skeptic." He never joined a church, and one political opponent, Peter Cartwright, accused Lincoln of what was called then "infidelity" in a congressional campaign. You can see Lincoln's response to that charge here. Personally, it seems to me that Lincoln would just rather avoid the whole subject and he does not really answer the charge, thus lending some credence to the idea that Cartwright's allegations were true.

Now, when Lincoln is campaigning against the extension of slavery into the territories in the 1850s he frequently attacks, or mocks, the idea that slavery is a divine institution and good for the slave (e.g. pro-slavery theology). I especially like the sentence in the preceding link where he says that "Certainly there is no contending against the Will of God; but still there is some difficulty in ascertaining, and applying it, to particular cases." Thus, he condemns slavery's defenders for using God to mask their own self-interest. During the Civil War, I think Lincoln's language becomes much more suffused, if you will, with religious imagery. In a sense, how could it be otherwise? Hundreds of thousands of Americans are dying (this would be millions, proportionally speaking, today) and he had to make sense of all this suffering and communicate it to the American public in religious language. The culmination of this is his Second Inaugural Address, which some historians believe is truly his greatest speech. Notice Lincoln's sense that the war is God's just punishment for the sin of American rather than southern slavery. It is a remarkable address, yet one without rancor and closing with perhaps the finest peroration in the English language.

Once the war concluded and Lincoln had been assassinated, then the issue of his religious beliefs became of profound importance for Americans. This is something that I explore in great detail in the second and fourth chapters of my book, Loathing Lincoln: An American Tradition from the Civil War to the Present. Lincoln's opponents accused him of being an "infidel," or unbeliever (this was true not only in the South, I might add), while some of his defenders claimed him as the quintessential Christian. Lincoln's law partner, William Herndon, tried to set the record straight in the aftermath of his friend's death, but in claiming Lincoln was not a Christian he made many people quite angry. Nowadays Lincoln's religious beliefs are interesting to Americans, of course, but I'm not sure they are as important to people (we are a much more religiously pluralistic country today, including those Americans who like Lincoln affiliate themselves with no church at all) as they were in the latter part of the nineteenth-century, or the early twentieth century. Still, I would agree with Christopher Hitchens that Lincoln cannot be enlisted in the atheist cause. He is instead a political figure who challenged those who claimed religious certitude, those who used religion to justify what was in their own self-interest, yet drew on religious tradition/language in attempt to ascertain the meaning of the Civil War for all Americans. Cocozzelli: Why would conservative Christian libertarians despise Lincoln? Barr: I think that it is because Lincoln and the Republicans used public power to intervene into a private arrangement - slavery. And, it seems to me anyway, that today many Christians are deeply suspicious of any government that might do something similar. Think gay marriage, for example. Also, I don't know that all, or even most, Christian libertarians despise Lincoln. To be sure, some do and they are influential, but I don't know if they are a majority. Cocozzelli: What about Lincoln's legacy teaches us how to effectively answer the Christian libertarian right? Barr: Consider these words from Lincoln: "Our government rests in public opinion. Whoever can change public opinion, can change the government, practically just so much. Public opinion, or [on] any subject, always has a "central idea," from which all its minor thoughts radiate."

The Author of Loathing Lincoln Explains Why Some on the Christian Right Loathe Lincoln | 3 comments (3 topical, 0 hidden)

The Author of Loathing Lincoln Explains Why Some on the Christian Right Loathe Lincoln | 3 comments (3 topical, 0 hidden)

|

||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||

print page

print page One under-reported result of the 2014 elections was the rise of Neo-Confederate politics in the U.S. This included the election of unabashed apologist for the Confederacy

One under-reported result of the 2014 elections was the rise of Neo-Confederate politics in the U.S. This included the election of unabashed apologist for the Confederacy